In November of 1829, two young boys were brought to Sylvester Manor by their mother, to be placed in indentured servitude. Their father Joseph, who was a member of the Pharaoh family of the Montaukett Indian tribe in East Hampton, had died, and their mother Esther Pharaoh made the decision to place William, age 8, and Isaac, age 5, with Samuel Smith Gardiner at the Manor. The Indenture agreement stated that the boys were bound to Samuel S. Gardiner until they were twenty-one years of age, and that he was responsible for housing, feeding and providing rudimentary education and skills to them in exchange for their labor. At the end of their service they would be entitled to twenty-five dollars and a new set of clothes. Esther Pharaoh signed the agreement with an ‘X’ as her mark.

In Samuel Smith Gardiner’s Daybook for 1828-1835, on November 16, 1829 he noted:

“I took this day from Esther Pharaoh, Squa, widow, two indentures, one for her son William and one for her son Isaac and have paid Esther twenty-five dollars in cash for William which is all I am to pay her except what the indenture requires on William arriving at full age and have paid her for Isaac seven dollars in cash… except what the indenture requires.”

Two days later Gardiner noted that he had paid Esther the total of seventeen dollars for Isaac.

The young brothers lived in the Manor House attic with other servants of the house, and perhaps in an area of the kitchen in cold weather. William and Isaac were close in age to the daughters of Samuel and Mary Catherine Gardiner, growing up in the Manor house with the three Gardiner girls, Mary, Phoebe and Fanny. We know few specifics about the lives and duties of the boys. Reference to them was made in letters written by the Gardiner girls and by their grandmother Mary Catherine L’Hommedieu and, a generation later, in family memoirs written by Mary and Phoebe Gardiner’s daughters.

The letters note that the boys suffered from a form of rheumatism and were in bed frequently with aches and pains – perhaps because of their living conditions in the uninsulated attic, which still today is freezing cold in winter and stifling hot in summer.

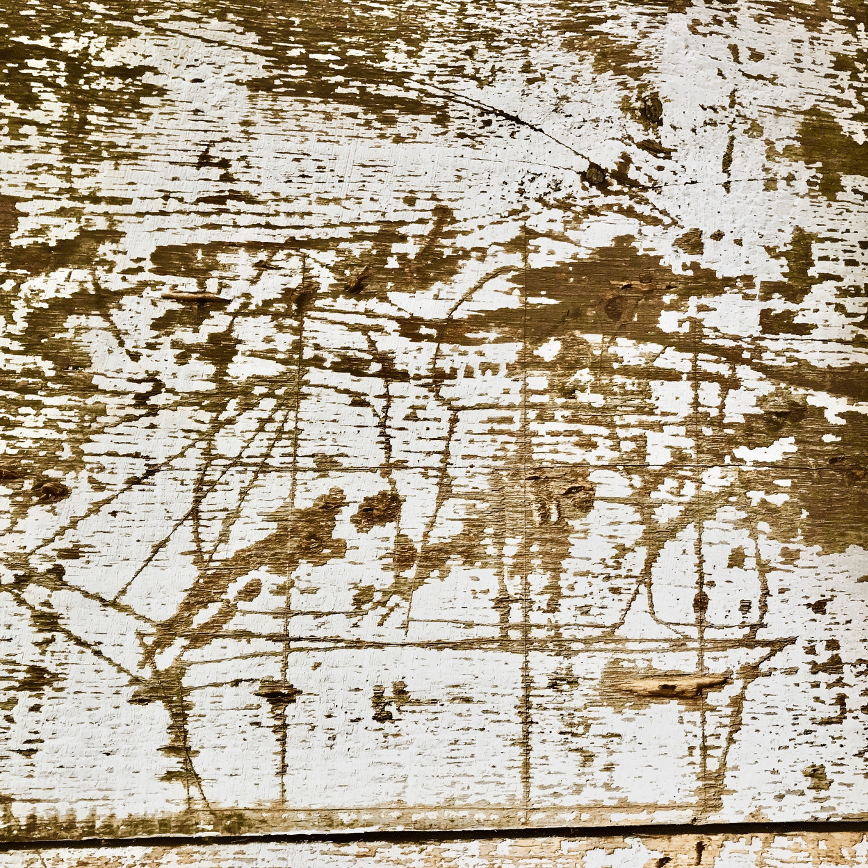

Despite the scarcity of documentary evidence of their lives, their presence is powerfully felt today in the form of “ship graffiti ” carved into the attic walls, long attributed to the Pharaoh brothers. Forty-three ships have been counted; some of them extraordinary examples of ship carvings in great detail; sailing ships the boys may have seen when they visited the nearby ports of Greenport or Sag Harbor. The etchings are a powerful visual legacy of the boys’ lives in the attic, and of the longing they must have felt to be free. The name “WM Phar ” is etched in the alcoves most densely covered with ships.

In August 1840, Mary and Phoebe Gardiner journeyed upstate with their father, to the Albany Female Academy and their new lives at boarding school. A note dated August 24, 1840, written in a frantic scrawl by the girls’ grandmother, Mary Catherine L’Hommedieu, to her son-in-law Samuel Smith Gardiner, reported that William ran away two days after the girls’ departure:

“Dear Sir, I must state to you an unpleasant event that has taken place since you left home on the 19th…On the 22, Saturday morning we could not find your William…I hope you will find ought [sic] how he got off the Island.”

The previous day William and Isaac had been to Greenport and were seen talking to the crew of a sloop sailing that night to New London, Connecticut. The brothers returned home to the Manor and went to bed in the attic. The next morning, William and his belongings were gone. He had crept down the stairs, past the bedroom that Mary and Phoebe had occupied before their departure, and made his way out of the house, presumably to meet the departing ship.

That August, William was nearly 19 years old, and his Indenture would end in just 18 months, in February 1842. But his yearning to leave the Manor and be free outweighed all other considerations. The girls, whose names are etched along with William’s in the attic boards by the ship graffiti, had left for school and when the chance came for William to seize his freedom, Sylvester Manor could no longer hold him.

Sixteen-year-old Isaac stayed or was left behind at the Manor. He fulfilled his indenture term, and continued to live at Sylvester Manor for the rest of his life. Mary Gardiner Horsford’s daughter Lilian remembered him as an “old Indian man who worked for their grandfather Samuel.”

Isaac Pharaoh is believed to be one of the last persons buried in the “Burying Ground of the Colored People of the Manor.”

For many years the story of WIlliam’s running away was where the paper trail ended until this year as we devoted more time to deep research. Searching the whalinghistory.org website, we found William’s name listed as a crew member on whaling ships out of New London. Excitedly we discovered that he had served on a whaling voyage starting the month after he ran away from Shelter Island!

Upon arriving in New London in August, William signed onto the crew of the ship Superior which left port in late September 1840. He lied about his age, saying he was 21 years old instead of 19, and spelled his name phonetically as William Faro. The crew list describes him as being 5 feet 9 inches tall, an Indian from Long Island. The Superior’s whaling two year voyage was bound for the South Atlantic and when it returned to New London in July 1842, William signed on again as a crew member aboard the ship Jason. A month later it left port to hunt whales in the Atlantic rounding the tip of South Africa into the Indian Ocean. Ship logs show that Jason went as far as the islands of Madagascar and Mauritius and returned to New London in May 1844 when William would have been 23 years old.

This new information about William Pharaoh and the proof that he was able to follow his dream of going to sea was an incredible finding…and is evidence that there are many great stories just waiting to be discovered and told!

For more on the second voyage of William Pharaoh aboard the Jason visit WhalingHistory.org

Post Office Box 2029

80 North Ferry Road

Shelter Island, NY 11964 info@sylvestermanor.org 631.749.0626