When sixteen-year-old Grizzell Brinley married Nathaniel Sylvester in 1653, and came with him to Shelter Island she brought with her an enslaved African family that she herself owned – Hannah and Jacquero, husband and wife, and their daughter Hope. No documentation has come to light describing how or where Grizzell acquired this family, but it is thought that her brother Francis who had done business with the Sylvesters and their partners in Barbados before moving to Newport brought the small family with him from Barbados with the intention that they would serve his sister in her new household. They were not part of her dowry or marriage agreement and remained her personal property for the rest of her life. Nathaniel and Grizzell were the first Europeans to colonize the Island that was the home of the indigenous Manhansett people. Hannah, Jacquero and Hope arrived with Grizzell and Nathaniel and together they established what was to become Sylvester Manor.

Due to the lack of documentation, reconstructing the lives and histories of Hannah and Jacquero is left to surmise and the imagination. Their names, listed on Wills and inventories are our only clues. One or both of them may have been born in Africa and brought to the West Indies across the Middle Passage. It is also possible that they were from the early generation born into slavery on Barbados. Jacquero’s name suggests that he was a captive of Spanish or Portuguese enslavers before being sold to the English. Hannah’s English name may be an indication that she was creole born in Barbados. The appeal of them for Grizzell as a couple and family group was likely in Hannah’s experience in tending to household tasks, childbirth and child rearing and most importantly, her ability to speak English sufficiently to communicate with Grizzell.

Leaving her family in London, Grizzell would have had limited knowledge of how to carve out a life and household in the wilderness of Shelter Island, where the Sylvesters were starting from scratch. Along with her enslaved and indentured servants, African, Barbadian and Indigenous, Grizzell was isolated and alone with Nathaniel on the island. The young bride would have needed to rely on Hannah and her skills; Hannah would have provided her with service, experience and perhaps companionship as well. Perhaps Hannah served as midwife and wet nurse to Grizzell and Nathaniel as they brought twelve children into the untamed world of Shelter Island.

The purchase of the African family as a group can be seen as a glimmer from Grizzell of what later attracted her to the teachings of the Quakers. In the 17th century, Quakers were not the fierce abolitionists they would become in the 18th and 19th centuries. They preached that white slave holders needed to treat the enslaved with kindness, and see to their needs with more charity, to thus instill loyalty and obedience instead of by cruelty and poor treatment. They didn’t preach against the idea of owning people, only addressing the ways the enslaved were treated. Grizzell and Nathaniel’s adherence to Quaker principles can be seen in the acknowledgement outlined on Nathaniel’s Will of the family groups of the enslaved at the Manor.

Grizzell’s 11 surviving children may well be testament to the care and treatment she and they received from Hannah over the years. Hannah herself only gave birth on Shelter Island to one other surviving child, another daughter named Isabell. She is listed as the daughter of Hannah and Jacquero but also as the property of Nathaniel Sylvester. She is therefore among the first generation of children of African descent born on Shelter Island. These children, Hope and Isabell, grew up along with the Sylvester children, and perhaps also with native Manhansett children that still resided on the Island.

We don’t know how old Hope was when she arrived with her parents and Grizzell on Shelter Island, or where she was born. Either she was too young to be separated from her mother when she was placed in Grizzell’s service, or she was old enough to have been able to work in the house as well. Whatever the circumstances, we know that Shelter Island was the only home she knew growing up. The traditions taught to Hope and her sister by their parents were the only link they had to their African heritage, and those lessons likely were kept hidden; a secret within their family group. Would Jacquero have taught them words from his own language, or the history, songs and beliefs of his African ancestors? On cold winter’s nights would Hannah speak of the warm breezes and blue seas of Barbados? We can only surmise what the lives and relationships were of these sisters, but given that they were kept together in one place for so many years, it seems possible that something of their heritage was passed on to them.

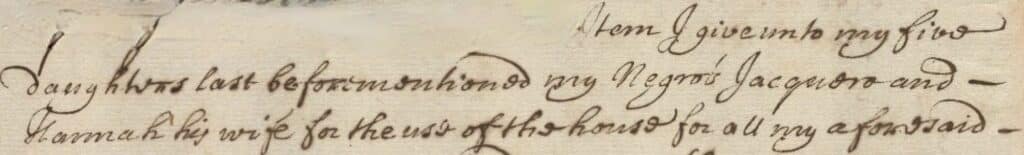

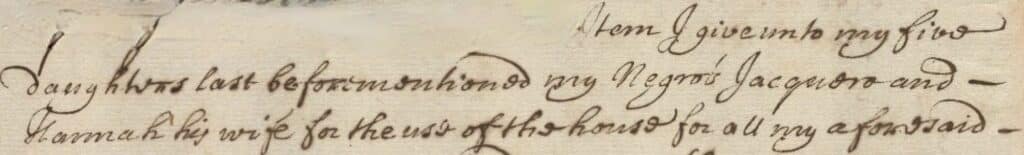

When Nathaniel Sylvester died in 1680, his Last Will and Testament bequeathed the enslaved families to his wife Grizzell and their children. The Sylvester children who received bequests in the will ranged in age from 11-year-old Ann to 24-year old Giles. The majority of the enslaved children were bequeathed to the Sylvester daughters with the provision that possession would occur when they turned 21 or were married. The enslaved married couples were given to Grizzell, and to the eldest sons. Although the bequests separate the enslaved family groups, they were all still living together at the Manor compound.

Hannah’s daughter Isabell was given to 14-year-old Elizabeth Sylvester, and when she married in 1686, Isabell went with her to live in Southold. This was perhaps the first time the family had been separated since arriving on Shelter Island. Grizzell died in 1687 and her Will bequeathed Hope to her daughter Elizabeth as well. Hannah and Jacquero were left to her three unmarried daughters still living at the Manor.

In the 1698-1700 Southold Census which included Shelter Island as well, nine of the enslaved people named in Nathaniel’s Will are listed as “Slaves.” Hope’s name is on this list but Elizabeth Sylvester and Isabell are listed on the Southampton census. Elizabeth’s first husband had died, and she soon married again and moved to Southampton. Why she was unable to take Hope with her and Isabell is unknown. Perhaps Hope’s age by this time was a factor in her being left behind on Shelter Island. Or Elizabeth’s husband was unwilling to take on the care of an additional person who could not provide him with service. This is the last documented reference to Hope and Isabell that we have found so far.

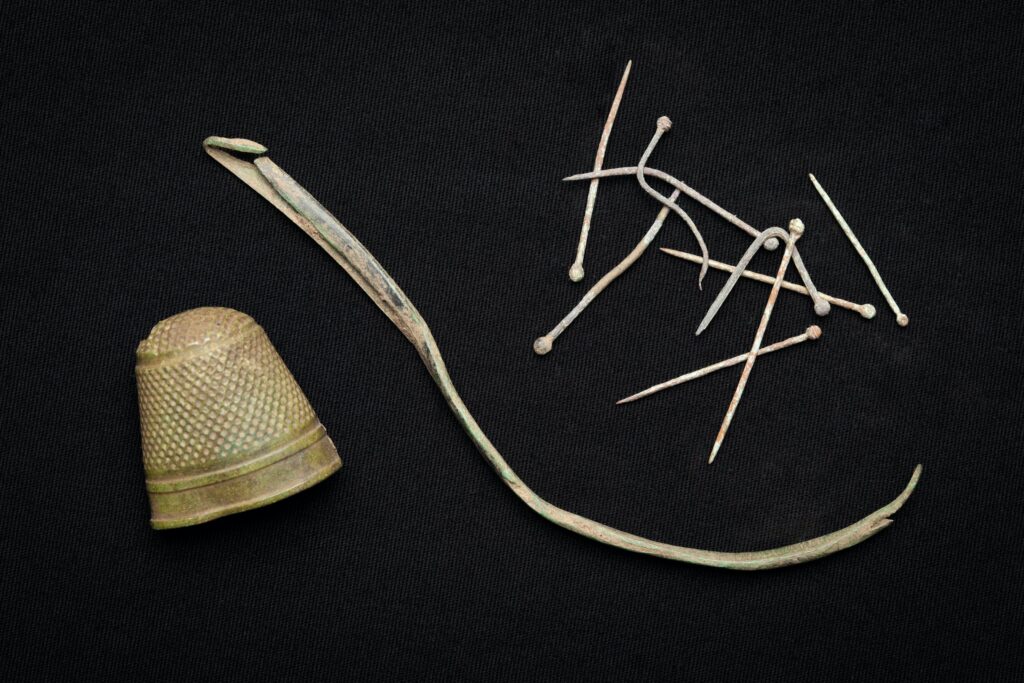

Hannah and Jacquero probably never left Shelter Island after they arrived in 1652 and they remained enslaved and connected to the Sylvester family for the rest of their lives. The dates of their deaths are unknown but they were mentioned in Grizzell’s 1687 Will and Jacquero’s name appears again in an account book of Giles Sylvester with an entry dated 1689, listing a payment of cider for an unnamed service. We believe that they are buried in unmarked graves in the Afro-Indigenous Burying Ground at Sylvester Manor.

We honor them as Ancestors and Founders of this place.

Post Office Box 2029

80 North Ferry Road

Shelter Island, NY 11964 info@sylvestermanor.org 631.749.0626