The History & Heritage staff at Sylvester Manor, with funding support from the Mellon Foundation in 2022, has been able to conduct deeper and more successful research than ever before into the lives of the enslaved and free people of color of Sylvester Manor, in Shelter Island, New York and nearby areas. Among the work over the past year – with research from church and legal records, account books, inventories and family letters – we have been able to uncover the lives and history of a family of four generations of women who all lived and worked at Sylvester Manor at some point in their lives, tracing them from slavery to freedom to burial at the Manor’s Afro-Indigenous Burial Ground.

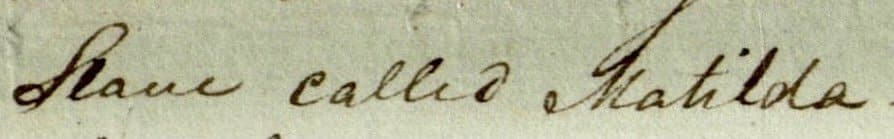

The story begins in Southold in the 1751 Presbyterian Church records documenting the baptism of an enslaved black woman named Judah along with two of her daughters, Dorcas and Matilda (recorded as Matillo and later as Matilla). Judah and her five children – Dorcas, Matilda, Violet, Thankful and Shuboul – were enslaved in the household of John Corey, a prominent and deeply religious Southold resident and a member of a large East End family on Long Island. Judah’s baptism is among the first records we have found of an enslaved person being admitted to the Southold Presbyterian Church which also records all of her children being baptized in the following years.

When John Corey died in 1754, his Last Will and Testament instructed that Judah was to be bequeathed to his wife, Dorothy; and Judah’s daughters, Matilda and Violet, given to Corey’s daughters. Judah’s son Shuboul was given to Corey’s son Abijah. Instructions in the Will also stated that Judah’s remaining daughters, Dorcas and Thankful, were to be sold away from the family. Records show that in 1753 Judah’s children ranged in age from 4 to 14 years old. There is no indication of who the father of Judah’s children was; no enslaved adult male appears in John Corey’s household.

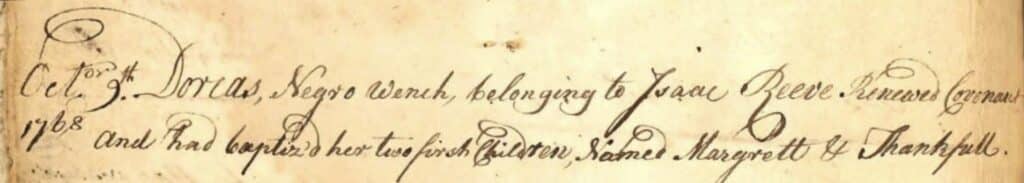

Separated from their mother, sisters and brother, Dorcas was sold to Issac Reeve, another Southold resident. Thankful’s buyer is so far still unknown.

By 1765, John Corey’s widow and daughters had all died. Violet and Matilda were sold: Violet to Nicoll Havens and Matilda to Thomas Dering, both property owners on Shelter Island. Matilda’s name appears on Dering’s 1765 property inventory for Sylvester Manor with her value listed as 50 pounds. An older woman identified as “Judith” also appears on the inventory with a value of just seven pounds. In the same time frame, Violet appears on a listing of the Havens household also with an older woman listed named “Judith.”

We believe that this woman listed as “Judith” is their mother, Judah. The Dering and Havens families were close neighbors, and it is possible that Judah moved between both households living with one of her daughters.

In an undated 19th-century diary entry written by Nicoll Havens’ nephew Lodowick, he writes that his uncle kept “Negro slaves” and lists their names as Violet and Judith. While Violet and Matilda were living on Shelter Island, their sister Dorcas was still enslaved in Southold in the Reeve household. A 1768 Mattituck church record mentions that her two daughters, Margrett and Thankful, were baptized in the church. No father is listed but Dorcas named one of her daughters after her own sister, Thankful, who had been sold away after John Corey’s death. Her daughter Margrett would come to be known as Peg and eventually all would move to Shelter Island and live as free women.

Matilda and Hagar

Judah’s daughter Matilda was born enslaved in Southold circa 1748 into the household of John Corey. When Thomas Dering made his inventory in 1765, Matilda would have been close to 29 years old. Ten years later, when the family fled to Connecticut in exile during the Revolutionary War, we believe that Matilda was one of the enslaved people left behind to tend and protect the Manor house and property when the British troops invaded and occupied Shelter Island.

It may have been during this time period that she became involved with an enslaved man named Caesar who lived at the Havens house. During the Revolutionary War, which lasted seven years (during which the Dering and Havens families were exiled), Matilda and Caesar had a daughter named Hagar.

After the Revolution, and ten years after the death of Thomas Dering in 1785, Matilda was finally manumitted by Dering’s sons Sylvester and Henry Packer Dering. She borrowed $75.00 from Henry for materials to build a house on leased land owned by his brother Sylvester, immediately indebting herself to the very men who had enslaved her. Caesar, who had gained his freedom after Nicoll Havens died in 1783, married Matilda in 1800. Their marriage was recorded in the Southold Presbyterian Church records, which states they were married on Shelter Island. They worked together to make a living, and to pay off the debt and rental of their property.

Their still-enslaved daughter Hagar was brought to Sag Harbor to work in the house of Henry Packer Dering, who served as the first U.S. Customs Master. Dering manumitted Hagar in 1802, and she continued to work for him until 1809. In an 1806 letter from Ebenezer Sage, a Sag Harbor resident, Dering wrote that, “Hagar reports that the old cow is on the decline.” And in 1807, Dering wrote to his son that “Hagar has returned home,” meaning she returned to Sylvester Manor. We believe that Hagar gave birth to a daughter named Jane on Shelter Island in July of 1808. There is no documentation of Hagar working for Henry Packer Dering or any other reference to her beyond 1809, so it is likely that she died sometime after the birth of her child, Jane.

Like her mother Judah, Matilda became a full member of the Shelter Island Presbyterian Church in 1814. She is listed in the 1800 and 1810 U.S. Census as being a free woman of color and the head of her household. Her death in 1818 is listed in church records, and she was buried in an unmarked grave at the Afro-Indigenous Burial Ground at Sylvester Manor. Matilda’s husband Caesar was also buried there when he died in 1827. There is no way to tell if they were buried near each other.

Violet and Jane Havens

Judah’s daughter Violet was born enslaved in Southold in 1741. She was purchased by Nicoll Havens of Shelter Island after his first wife died in 1767 to care for his young children including four-year-old Esther Sarah and two-year-old Mary Catherine. From their young ages, the sisters formed a bond with Violet that lasted her whole life and they remained committed to providing for her and her needs.

When Esther Sarah married Sylvester Dering in 1787, she moved to the Manor House and brought Violet and her mother Judah to live with her. Following the wedding, her mother-in-law Mary Sylvester wrote to her son Henry, who was in Haiti at the time: “The servants all rejoice to hear of your arrival and ask when you are coming home. Old Judah bids me tell you she prays for you.” This is the last documented record we have of Judah.

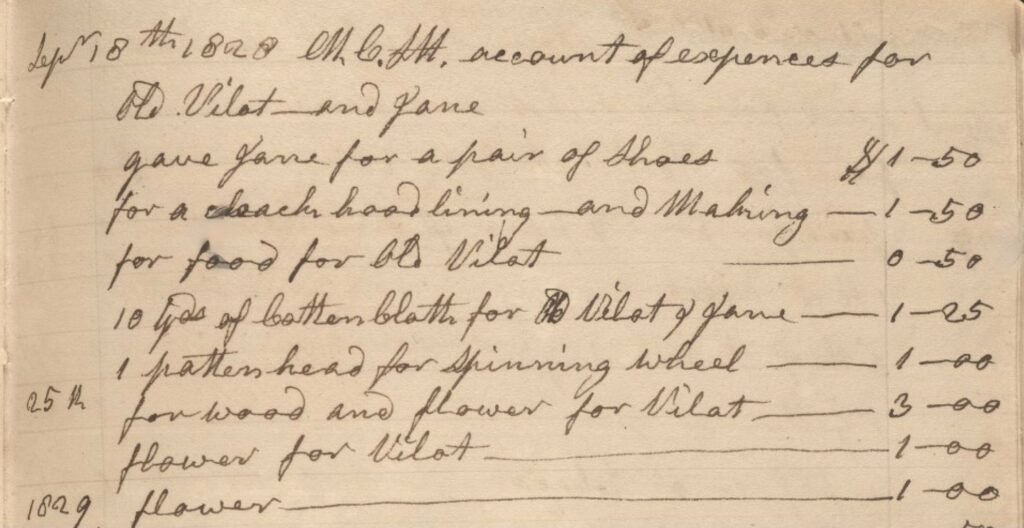

Sylvester Dering manumitted Violet from slavery in 1806 when she was 65 years old. Sisters Esther Sarah and Mary Catherine continued to care for her and Mary Catherine frequently made inquiries of her brother-in-law as to what she could contribute to Violet’s care. Letters between family members mention Violet frequently, expressing concern for her health, comfort and living arrangements. In the account books of both sisters, many pages are dedicated to the care and well-being of Violet who was gradually losing her sight. They list the supplies they provide her, including regular quantities of rum, flour, cloth, molasses and Souchong Tea. Hagar’s daughter, Jane – great-niece of Violet – was also mentioned, with Mary Catherine paying for Jane’s clothing and schooling by a private tutor.

There is no evidence that Violet had children of her own, but the love and affection shown to her by Esther Sarah Deringand Mary Catherine L’Hommedieu are evidence of her influence and importance in the lives of her former enslavers. Violet was considered a member of the Sylvester family. Both Esther Sarah and Mary Catherine were strong, faith-filled women, each managing their family’s estates after the deaths of their husbands. That Violet remained such a presence is testament to her significance in their lives.

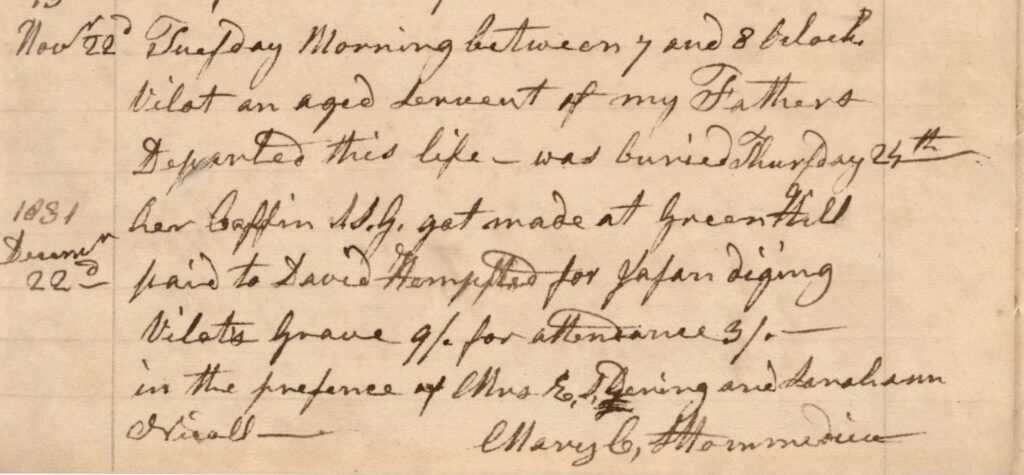

Violet, whose name is recorded as Violet Havens in the 1820 Census, died on November 22, 1831 at age 90. Mary Catherine wrote in her journal that Violet, an aged servant in her father’s house, died between 7 and 8 o’clock in the morning and that her grave was dug by David Hempstead and his sons in the Burial Ground at Sylvester Manor. Violet’s funeral was attended by Mary Catherine and two of her sisters. Despite their obvious love for Violet, she too was anonymously laid to rest in an unmarked grave.

After Violet’s death, 23 year-old Jane Havens continued to live in a house at Sylvester Manor that she and her great aunt had occupied for many years. It was owned at the time by Esther Sarah Dering’s son, Charles Thomas Dering. In an 1839 letter to Samuel Smith Gardiner, Dering states that he intends to gift the house to Jane and described her as “so faithful a person (as I consider her to be).” Gardiner, however, objected to this arrangement and soon afterwards Jane moved to Sag Harbor to live and work for Charles Thomas Dering. Jane was eventually able to purchase a house in the Eastville community of Sag Harbor that was later bought by David Hempstead Jr.

Jane Havens died in 1875 at the age of 66 and was buried in the Oakland Cemetery in Sag Harbor alongside Eliza Dering’s sisters in the Nicoll family plot. After a lifetime of freedom and service to the Dering family, her weathered headstone bore the following inscription:

“Jane Havens, colored, was born on Shelter island, July 15, 1808,

died April 10, 1875, a faithful, honest, family servant, also a follower of Jesus.”

Dorcas and Thankful

As of now, we have found few records of Judah’s daughter Dorcas. We know she was sold to Issac Reeves in 1753, and her daughters Margrett and Thankful were baptized at the Mattituck Presbyterian Church in 1768. Her son Silas (or Siras) was baptized in 1772 at the same church as an enslaved child belonging to Reeves.

Thankful was manumitted from slavery in the early 1800s and she married a man named Peter in Shelter Island in 1811. Peter had been bought by Henry Packer Dering in 1810 and manumitted shortly thereafter. A woman named Dorcas is known to come to live on Shelter Island around this same time, but so far the only information we have of her life is that she died in 1825.

Both Peter and Thankful became members of the Shelter Island Presbyterian Church and worked at Sylvester Manor. We do not yet know if they had any children. Thankful died in 1819 and is buried at Sylvester Manor’s Afro-Indigenous Burial Ground. Peter died years later, in 1843.

Peggy Case

The baptism of Margrett, daughter of Dorcas and granddaughter of Judah, was on October 9, 1768 according to Mattituck Presbyterian Church records. Her sister Thankful was also baptized that day, and they were both enslaved by Issac Reeves.

More commonly known and referred to as Pegg, or Aunt Peggy, Margrett was later purchased by David Wiggins of East Marion. On April 26, 1798, she married a man named Jason who was enslaved by Moses Case until he was manumitted in 1806. Peggy gained her freedom around the same time, at the age of 50.

Upon gaining their freedom, Jason and Peggy Case and their children moved to Shelter Island to be closer to their extended family. They lived for over 50 years on the Island in a house provided by the Town of Shelter Island. Jason and Peggy had had at least two children, named Crank and Flora, while still enslaved. While not much is known of Crank and Flora’s lives we do know that they were named after another enslaved couple from Southold who came to Shelter Island to live after being manumitted. Jason and Peggy were also the parents of Diana Williams, a well known Black woman that lived on Shelter Island. A Sag Harbor newspaper article stated that Jason and Pegg’s daughter, Flora Case, drowned tragically with five others while traveling by boat from Sag Harbor to Shelter Island in 1833.

Blessed with longevity, Jason and Peggy lived more years of freedom together than enslavement apart. Peggy died in October of 1870, and she was noted as being the oldest person in Suffolk County to die that year. To note her passing, Sag Harbor’s newspaper of the day, The Sag Harbor Express, published the following:

“We learn by the Greenport Times that Mrs. Peggy Case, a colored woman, aged 103 years, died in that village on the evening of the 11th inst. Her husband, Jason Case, died on Shelter Island about eight years ago, at the Age of 102. They were both slaves for many years after their marriage. Pegg, by her own account until she was 50 years old, Jason belonged to the Case family of Southold and Peggy to the Wiggins estate in East Marion. For the last half century of their lives they resided on Shelter Island, and Peggy was boarded in that village at the expense of that town.”

Research Notes

Uncovering the story of Judah and her daughters has been an amazing and inspiring journey. Thanks in large part to a Officer’s Planning Grant from the Mellon Foundation in early 2022, Director of History & Heritage Donnamarie Barnes and Research Associate Alice Clark were able to spend hours, days and weeks reading personal letters, church records, inventories and histories. They constructed a database of names and circumstances that continue to fill out the stories of the enslaved and free people of color of Sylvester Manor, Shelter Island and the surrounding area. Names appear and reappear in many of the same documents, weaving together a narrative of interconnected lives.

We first learned about Matilda, her manumission and the debt to the Dering brothers from documents that are archived at the East Hampton Library. From there, we found her name in census and church records. The possibility that she and Violet may have been sisters soon emerged and shortly thereafter her relationship with Judah and other family members became clear. As is the case with most historical research, frequent coincidences often point to a reality. The name “Judith” or “Judah” was often found in combination with her daughters’ names, leading us to surmise that this was indeed the same person.

Uncovering the story of Judah, the matriarch of this incredible family of women, has been a gift from the Ancestors themselves. To finally be able to tell their stories, restoring to them a place in our collective history, has at times felt like an act of magic. The lessons Judah imparted to her children – despite enslavement, forced separations, deprivations, racism and hardships – is a testament to the woman she was, and to the gifts that she received from her parents, who were likely brought to these shores from Africa. These women remained connected to each other throughout their lives. They endured the bondage of enslavement and still found the way to be a Family. This was their resistance and their legacy, and we are proud to finally tell their remarkable stories.

This research was made possible through the assistance of many librarians as well as the following partners, organizations and archives. We are sincerely grateful for their ongoing support and assistance.

Plain Sight Project Database

Shelter Island History Center

Eastville Community Historical Society

East Hampton Library Special Collections

New York Public Library Special Collections

New York Historical Society

New York University Fales Library & Special Collections

Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute Folsom Library, Institute Archives & Special Collections

The University of Michigan Library, Special Collections and Archives

Ancestry.com

Special thanks to the Mellon Foundation and Humanities in Place Program for their support of this project.

Post Office Box 2029

80 North Ferry Road

Shelter Island, NY 11964 info@sylvestermanor.org 631.749.0626