Comus

Following the death of Nathaniel Sylvester’s grandson Brinley Sylvester in 1752, his married daughters Margaret Chesebrough and Mary Dering inherited the Sylvester property’s 1000 acres including the Manor House that Brinley had built c. 1735-37. Margaret and her husband David Chesebrough lived in Newport, Rhode Island, and Mary and Thomas Dering lived in Boston. During this time the Manor House and lands were leased to tenants to farm.

For ten years until 1762, the farm was leased by Phineas Fanning of Southold and worked by the black people he held in enslavement. When Thomas Dering’s business in Boston failed, the family terminated Fanning’s lease and decided to move to Shelter Island to farm the land themselves. Fanning returned to his own property in Southold.

According to his 1796 Last Will and Testament, Fanning granted manumission to his enslaved man, Comus, who took the last name Fanning upon gaining his freedom. It isn’t known if Comus had previously worked for Fanning at Sylvester Manor, but we do know that in 1800 he came to Shelter Island to work for Thomas and Mary Dering’s son Sylvester Dering.

Over the next twenty years, Comus Fanning saved the money earned from his labor as a free man, and by 1820 had saved enough to purchase 21.75 acres of land near Sylvester Manor from Dering at approximately $35 per acre. Documents held in the New York University Fales Library Sylvester Manor Collection describe the land purchased as “Beginning at a stake a little north of the outlet of Wilkinson Creek, with an existing house and garden.”

Comus Fanning paid Sylvester Dering $750 in cash, an enormous sum for his circumstances equivalent to approximately $25,000 today. A week after the land sale, Sylvester Dering fell from his horse and died from his injuries. For the next eight years the Dering family struggled to maintain the house and property but finally was forced to sell it due to overwhelming debts. Before the auction of the Manor property, Dering’s widow, Esther Sarah Havens Dering, signed a document confirming the land sale to Comus, protecting him from legal conflicts due to the sale.

When the Derings lost the Manor to Samuel Smith Gardiner and his wife, Sylvester descendant Mary Catherine L’Hommedieu Gardiner, Comus and Dido continued trade with the Manor, selling Gardiner wild turkeys, or buying wheat from him, as well as chopping wood while also working their own land.

Comus Fanning died on April 29, 1832, and we believe he is buried in the Afro-Indigenous Burial Ground at Sylvester Manor.

Dido

Dido was born into slavery in the household of Nicoll Havens on Shelter Island in 1772. Records indicate that her mother was an enslaved woman named Saviner who came to the Havens home when Nicoll married his second wife, Desire Brown in 1770. When Havens died in 1788, Dido was a teenager and she remained enslaved by his widow Desire Havens as her personal property. The other enslaved people in the household were divided among Nicoll’s children.

Dido, who was very close in age to Desire and Nicoll’s children, was frequently mentioned in family letters over the next decade as she traveled with Desire to Connecticut and New York City to visit the Havens children. Desire manumitted Dido finally in 1801 when she was twenty-nine years of age.

Sometime between 1808 and 1810, Dido gave birth to a daughter she named Julia. In years following, Julia’s race was listed on census records as Mulatto, indicating she had mixed-race parentage. Her father’s identity is not known, but it is more than likely that Julia was the child of an unnamed man from the Havens family. What his relationship with Dido was, will remain a mystery, but at the time of Julia’s birth, Dido had been a free woman for 8 or 9 years and was 36 years old. Although she never used the Havens name herself, Dido gave her daughter the surname of the family who had enslaved her and perhaps fathered her child.

Marriage and Death

After Julia’s birth, Dido married Comus Fanning and was known thereafter as Dido Fanning. The couple had one daughter together and named her Sophia. In the Shelter Island Presbyterian Church, where Dido was baptized and was a member, records indicate that Sophia died in 1818 with no age given.

During her marriage to Comus, Dido continued to be mentioned in letters between the Havens siblings that she had grown up with, in greetings and inquiries into her well-being. A mention in an 1820 letter from Sylvester Dering implies that Dido had traveled to New York City from Shelter Island presumably to visit Desire Havens at her son Rensselaar’s home.

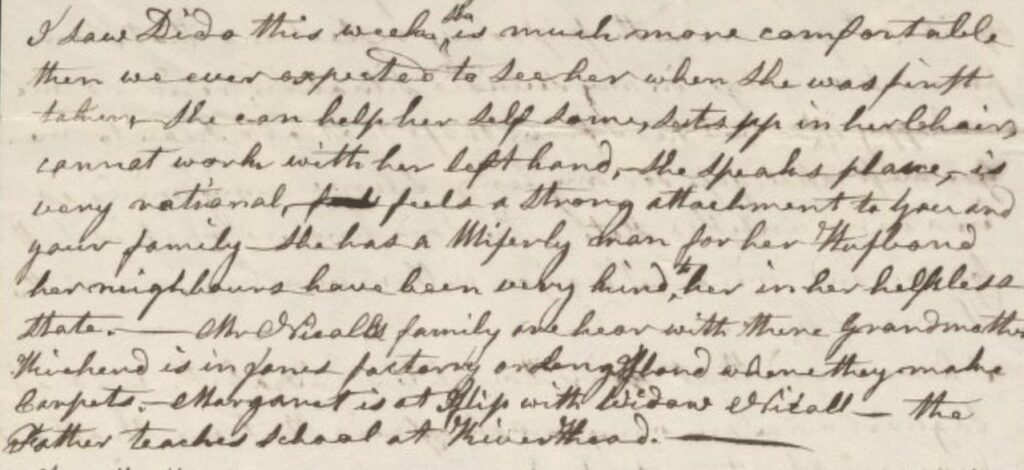

Through these family letters, we learned that Dido suffered a stroke in 1831 when she was fifty-nine years old. Mary Catherine Havens L’Hommedieu wrote to her sister Catherine Mary Huntington, who was very close to Dido growing up, to update her on Dido’s condition:

“I saw Dido this week. She is much more comfortable than we ever expected to see her when she was first taken. She can help herself some, sits up in her chair, cannot work with her left hand, she speaks plain, is very rational, feels a strong attachment to you and your family. She has a miserly man for her husband. Her neighbors have been very kind to her in her helpless state.”

The frequent updates and mentions about Dido in family correspondence –particularly among the Havens sisters – shows genuine affection and concern for her well-being.

When Comus Fanning died in 1831, his Last Will & Testament was written out by Samuel Smith Gardiner and Comus signed it with his mark. He left his land and house, “to my wife I now live with, Dido and to a daughter of said Dido named Julia who now resides with us.”

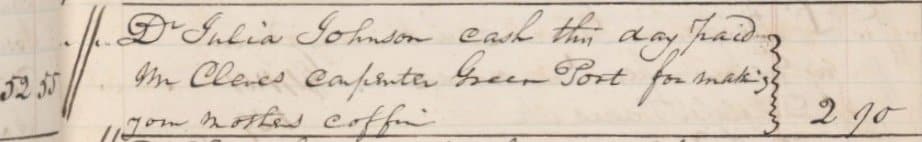

The property owned by Comus Fanning was the largest freehold owned by a black man on Shelter Island at that time. Dido died three years later in 1834, at age 62, leaving the house and land to her daughter Julia. Samuel Smith Gardiner’s account book at the time states that he charged Julia Havens $1.34 to purchase a casket for her mother in Greenport. Dido was buried at the Burial Ground at Sylvester Manor.

Post Office Box 2029

80 North Ferry Road

Shelter Island, NY 11964 info@sylvestermanor.org 631.749.0626